Church | XIV | Romanesque | Catholic Church

Map

Opening hours

01 January - 31 December

Mon 9.00 - 19.00

Tue 9.00 - 19.00

Wed 9.00 - 19.00

Thu 9.00 - 19.00

Fri 9.00 - 19.00

Sat 9.00 - 19.00

Sun 9.00 - 19.00

Description

In the middle of the countryside, at the gateway to the Bessin marshes, stands the church of Saint Marcouf, a charming little building with Romanesque origins.

Built as early as the 11th century, as can still be seen from the exterior walls of the chancel and nave, which are built in the so-called fish-bone bond, the parish church was originally a pilgrimage chapel dedicated to Saint Marcouf.

The church's large open doors, set in the middle of nature, are an invitation to enter and discover its wonders, from the superb 14th-century frescoes to the original 18th-century altarpiece, not forgetting the various representations of Saint Marcouf and the charming eagle-lutrin.

The bell tower was rebuilt in the neo-Romanesque style in the second half of the 19th century, inspired by those of Saint-Loup-Hors and Huppain. As you pass beneath the portal, look up to admire the beak-heads biting the edge of the arch, a very common motif in the region during the Romanesque period.

Photos

Remarkable elements

Frescoes from the 14th century

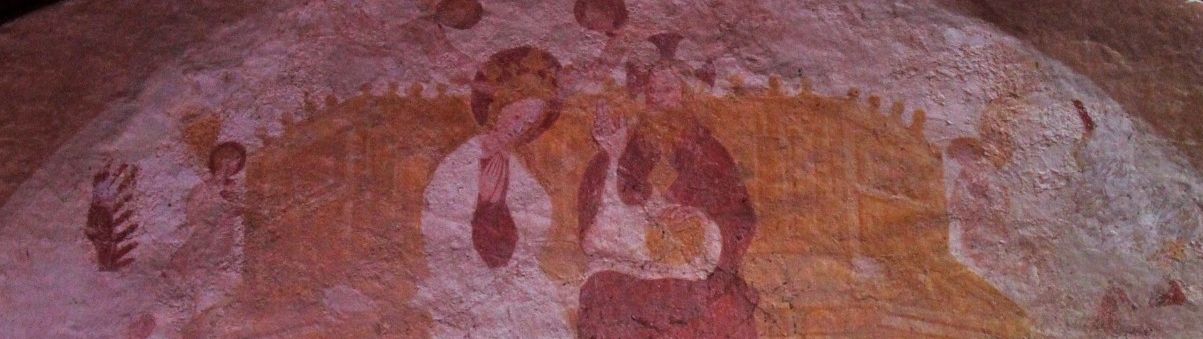

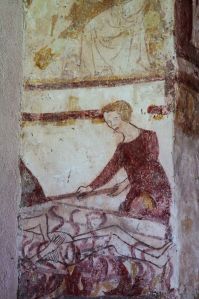

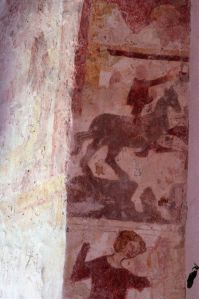

Rediscovered in 1957 when the high altar was destroyed, these 14th-15th century frescoes are the church's masterpiece and have since been listed as a Historic Monument.

The frescoes in the choir are very rich, depicting numerous scenes from everyday life or from the Bible, such as the Coronation of the Virgin and a representation of the Heavenly Jerusalem.

Statue of Saint Marcouf

In polychrome wood, dating from the 16th century.

The figure of this local saint is very important. Originally from Bayeux, he set off to evangelise the Cotentin region, where he founded a monastery. Legend has it that Saint Marcouf gave King Robert the Pious the power to cure scald, a thaumaturgical power that was perpetuated in France by kings right up to Charles X, during the Royal Touch ceremonies, with the famous phrase ‘The King touches you, God heals you’.

From then on, Saint Marcouf was invoked to cure the disease of écrouelles. A miraculous spring close to the building maintains this cult thanks to its pure water, which has the virtue of curing skin diseases.

Statue of Saint Louis

In polychrome wood, dating from the 18th century.

Saint Louis is depicted as a king wearing a blue coat dotted with fleurs-de-lis and lined with ermine.

He is holding Christ's nails, which belong to the elements of the Passion that he acquired and for which he had the Sainte-Chapelle built in Paris, a veritable jewel of radiant Gothic art and a sumptuous reliquary for the relics of the Passion.

18th century altarpiece

It was originally displayed in the choir, as it is the former altarpiece of the high altar dating from the 18th century. Flanked by Ionic pilasters and finials in the Rococo style, it features an 18th-century canvas depiction of the Resurrection, possibly from Rupalley's workshop.

12th-century tomb in the cemetery

‘In the cemetery, between the gate and the Yew tree, there is a very curious tombstone made of a block of sandstone; on this block is a cross, the cylindrical crosspieces of which are adorned at their ends with a sort of finial that seems to me to indicate the 13th or late 12th century’. Arcisse de Caumont, 19th-century historian and archaeologist from Calvados.

Five hundred year old yew

Yew is a highly toxic and harmful tree, but it is also very hardy, even if it grows slowly. It is no longer very common in France, but it is still very present in Norman cemeteries.

Harmful to livestock and crops, it is gradually disappearing from agricultural areas and is confined to the area around churches, which is a consecrated and often enclosed space. Traditionally, at least two yews were planted in cemeteries, one at the entrance and the other near the porch.

In addition, an ancient Celtic belief linked the longevity of this tree to the immortality of the soul. It was also thought that the leaves could absorb the odours and miasmas escaping from the body.